Happy Tuesday, and welcome to another edition of Rent Free. This past week is a rare one where all the major housing news is happening at the federal level. Major developments include:

- The announcement of the first round of "Baby YIMBY" grant awards, and housing advocates' disappointment at where this first tranche of money is going.

- House Republicans call for cutting federal housing programs, including total defunding of the enforcement of fair housing regulations.

- President Joe Biden's endorsement of "rent caps" in a debate performance made headlines for a lot of other reasons.

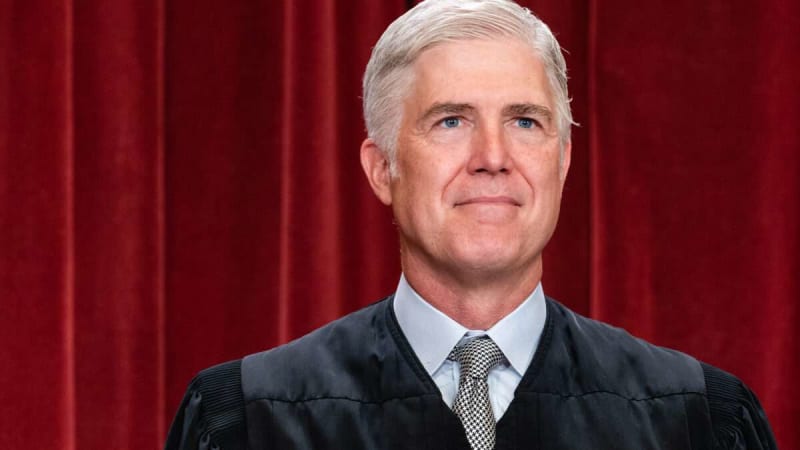

But first, our lead story covers the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, in which Justice Neil Gorsuch cites a lot of NIMBY government lies in a decision allowing more sweeping municipal crackdowns on the homeless.

NIMBY Governments Win at the Supreme Court

Last Friday, as Reason covered, the Supreme Court's six-justice conservative majority ruled that Grants Pass, Oregon's camping ban did not violate the Eighth Amendment to the U.S Constitution's prohibition on "cruel and unusual punishment."

The decision overturns two prior rulings by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit: the 2018 decision in Martin v. Boise that banned local governments from penalizing people for sleeping in public when there were no available shelter beds, and the 2022 decision in Johnson v. Grants Pass extending that prohibition to public camping bans that punished people for sleeping outside with rudimentary shelter or for sleeping in their cars when no shelter was available.

The Supreme Court's Grants Pass decision, written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, was the much-sought-after outcome for a wide constellation of local governments, their tax-funded associations, politicians of both parties, and more, who argued the Martin decision had left localities with little ability to police nuisances, get people into shelters, and provide public order.

Homeless and housing advocacy groups have decried the Supreme Court's decision as giving localities a blank check to criminalize and harass homeless people with no other options but to sleep outside or in their vehicles.

So, what to make of it all?

Gorsuch's Ruling: The Reasonable Legal Reasoning

The central question in the Grants Pass case is whether Grants Pass' public camping ban violated the Eighth Amendment's prohibition on "cruel and unusual punishment" by effectively criminalizing the status of homelessness.

The idea that the Eighth Amendment bans so-called "status" crimes comes from the Supreme Court's 1962 ruling in Robinson v. California, which struck down a California law that made it illegal to just be addicted to drugs.

In deciding Martin and Grants Pass, the 9th Circuit similarly reasoned that enforcement of camping bans when shelter beds were maxed out effectively criminalized the "status" of homelessness.

Gorsuch disagreed for two primary reasons. First, he said that Grants Pass' camping ban prohibits the actual conduct of camping in a park, not the status of being homeless. And its law applies to everyone.

Second, Gorsuch said the penalties for violating Grants Pass' camping ban (fines for initial violations and 30 days in jail for repeat offenses) were also run-of-the-mill criminal and civil penalties and not anything that could be considered cruel or unusual.

Since Grants Pass' camping ban didn't criminalize the "status" of homelessness, and it didn't levy cruel and unusual punishments, it didn't violate the Eighth Amendment, he concluded.

Reasonable minds can disagree with Gorsuch's analysis. Justice Sonia Sotomayor certainly does in her dissent. But his decision strikes me (a non-lawyer) as a reasonable parsing of the Eighth Amendment issues raised.

Gorsuch's Ruling: The NIMBY Throat-Clearing

Gorsuch's opinion takes a while to get to those Eighth Amendment issues, however.

His opinion opens with a lengthy explanation of why the 9th Circuit's Martin decision has made the problem of homelessness so much worse. In short, he argues that it has tied the hands of local governments, who have one less "tool in the toolbox" to get people off the streets.

In making that point, Gorsuch uncritically cites odd, contradictory, and false claims from municipal governments about why they're failing so hard at addressing homelessness.

He cites claims from several California cities that Martin makes it harder to persuade people to accept shelter beds. That's despite the Martin decision only banning local governments from enforcing bans on sleeping outside when there are no shelter beds available.

He cites the League of Oregon Cities' claim that because of the Martin decision, the homeless will reoccupy cleared encampments after a couple of days. That undercuts the notion that Martin was preventing encampment clearings in the first place.

Gorsuch quotes from an amicus brief filed in September by the city of Phoenix that Martin and Johnson have "paralyze[d]" its efforts at addressing homelessness.

Yet, just a few days before Phoenix filed that brief, a Maricopa County Superior Court judge ruled the city was incorrectly citing Martin and Johnson as an excuse for not clearing permanent encampments and policing public nuisances—two things it still very much had the power to do.

Bad Faith Local Governments

Phoenix's amicus brief in the Grants Pass case was co-written by the League of Arizona Cities and Towns—a taxpayer-funded lobbying group that spent most of this past year fighting efforts in the Arizona Legislature to liberalize local zoning codes.

Local governments love to blame Martin for rising homelessness because it relieves them of any real responsibility for the problem. Homelessness is something that happened to them, and here comes the 9th Circuit preventing them from doing anything about it.

It's an incredible act of blame-shifting. In fact, local and state governments bear a considerable share of the blame for the rising homeless population by making housing so hard to build in the first place.

Nothing correlates more with homelessness rates than high housing costs. And nothing drives up housing costs like government restrictions on building housing.

When getting city approval for a new apartment building takes two years, state environmental law lets anyone delay an approved project with lawsuits, and the cheapest forms of housing are banned completely, is it any surprise that thousands of people end up on the streets?

Where cities and states regulate building less, housing costs are lower, homeless populations are smaller, and dealing with homelessness (whether that's through providing more shelter beds or more effectively policing nuisances) becomes cheaper and more manageable.

Lifting restrictions on building homes is something local governments could easily do on their own initiative. They could do that without giving anyone cause to complain about cruel and unusual punishment.

The same municipal associations saying Martin needs to go are the same municipal associations that fight tooth and nail against even the most modest land-use deregulation.

Questions of Scale, Not Approach

Giving police greater powers to ticket and arrest anyone sleeping on a park bench isn't going to fix homelessness when you're in San Francisco and 4,000 people in your city are sleeping outside, the median apartment rents for $3,300 a month, and the number of new homes permitted per month is in the single digits.

Nor, frankly, will "housing first" strategies fix homelessness in high-cost cities with the highest homeless rates. Those high housing costs make providing supportive housing incredibly expensive while generating more and more homeless people all the time.

Realistically, the only way homeless rates can come meaningfully down is through serious land use liberalization that boosts home building and brings housing costs down.

Once that happens, many different approaches to homelessness become more politically palatable, more workable, and more humane.

It's less cruel and unusual to fine someone for pitching a tent in a public park if they are offered a shelter bed first and, with perhaps a little help, they could be in a position to afford a place of their own. Conversely, public order and citywide quality of life aren't as threatened by municipal toleration of the handful of people who do keep sleeping on the streets.

Until local and state governments adopt policies that would significantly reduce the costs of housing, it is unfair, unhelpful, and illiberal to fine people for sleeping on a park bench with a blanket—even if doing so is constitutional.

New 'Baby YIMBY' Grant Program Rewards NIMBY Policies

In late 2022, Congress created a new $85 million program that would reward jurisdictions that removed regulatory obstacles to new housing construction with grants that would pay for removing even more obstacles.

This past week, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) published the list of jurisdictions that received the first Pathways to Removing Obstacles to Housing (PRO) grants. The list is not encouraging.

In many cases, HUD is paying jurisdictions for adopting policies that make it harder, not easier, to build housing. Grants are also going to fund vague planning activities that won't enable the creation of new units.

"Some were disappointed when they heard this was going to be a small grant. Boy is it good that we started small, because we can learn from this," says Alex Armlovich, a housing policy researcher at the Niskanen Center.

Questionable Recipients

In explaining why it gave Philadelphia a $3.3 million PRO grant, HUD identified the city's "inclusionary zoning" (I.Z.) requirement that 20 percent of newly constructed housing in some neighborhoods be offered at below-market rates to lower-income residents.

Philadelphia's affordability mandates, which act as a tax on new development, have been identified as a major barrier to new housing.

"Philadelphia, among large cities, is one of the last ones moving sharply in the wrong direction," says Armlovich. Yet here the city is, receiving a $3 million PRO grant.

New York City and Seattle also received PRO Grants because they'd adopted inclusionary zoning policies, despite both cities' I.Z. programs also being identified as barriers to housing construction. (Seattle is currently getting sued over its I.Z. program.)

The state of Hawaii received a $6.6 million award (the second largest award) because of emergency orders issued by Gov. Josh Green that suspended local housing regulations and created a state body to expedite the approval of projects.

Greens' emergency orders excited a lot of zoning reformers when they were first issued. (I dubbed them "YIMBY martial law.") But, in response to lawsuits and concerted opposition, Green quickly reimposed many of the regulations he'd additionally waived. Sen. Brian Schatz (D–Hawaii) was the author of the PRO Grant program.

Unproductive Awards

Many of the local programs funded by PRO Grants are also of questionable value.

Iowa City, Iowa, will receive a grant to study whether minimum parking requirements drive up the cost of new housing. (We already know that they do.) Philadelphia's grant will pay for studying whether its I.Z. program (which, again, HUD identified as allegedly removing obstacles to new housing) is in fact making some new housing economically infeasible.

Anaheim, California, is getting money to create a "city livability lab."

Some of the planning work funded by PRO Grants is better targeted. New York City will get money to fund the implementation of its pending "City of Yes" zoning reforms. The Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments' $3.5 million award will fund the implementation of several localities' "missing middle" reforms that allow multi-unit housing in single-family areas. Denver is getting money to hire more planning staff to process permits faster.

Nevertheless, "looking at all of these, it's very ambiguous how much housing is going to come from these grants," says Emily Hamilton, a housing policy researcher at George Mason University's Mercatus Center.

Potential Fixes

Hamilton suggests one way the PRO Grant program could be improved: "I think the federal government could do a lot better by looking at rewarding housing market outcomes rather than planning activities that are just very difficult to forecast how they'll affect housing supply."

Practically, that would mean giving grants to high-demand jurisdictions that are approving the most new housing and low-demand jurisdictions that are approving moderately priced new housing.

Armlovich suggests that Congress could improve the PRO Grant program by passing the YIMBY Act, which requires recipients of federal housing funds to report on whether they've adopted pro-supply policies like eliminating parking minimums or shrinking minimum lot sizes.

That would provide clearer "legislative intent of what it means to lift supply barriers," he says. "We can point localities and HUD grant reviewers to the YIMBY Act's list of actions." The YIMBY Act passed the House Financial Services Committee unanimously in May.

House Republicans Propose Modest Cuts to Federal Housing Spending

Whether the PRO Grant program lives long enough to be reformed is an open question. House Republicans' latest budget proposal) calls for totally eliminating the program as part of $2.3 billion in cuts to HUD's budget.

That's a 3 percent reduction in HUD's budget compared to this year's funding levels, says the National Low Income Housing Coalition in an analysis.

In addition to axing the PRO Grant program, House Republicans' proposal would also end funding for HUD's "green new deal" for public housing and grants to local legal services organizations that aid tenants facing eviction.

Tax-funded legal service providers have received a lot of criticism for deliberately slowing down housing courts and effectively forcing landlords to house non-paying tenants.

House Republicans also propose blocking any funding of enforcement of the Biden administration's "Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing" rule, which requires jurisdictions to report on barriers to "fair housing."

Biden Endorses Rent Control at First Presidential Debate

At last week's presidential debate, President Joe Biden endorsed rent control in his first answer of the night.

"We're going to make sure that we reduce the price of housing. We're going to make sure we build 2 million new units. We're going to make sure we cap rents, so corporate greed can't take over," said the president.

In April, the White House finalized new regulations that impose new income eligibility caps for residents at federally subsidized affordable housing developments. Because rents at subsidized housing are tied to residents' incomes, this is a de facto rent cap.

That has the effect of limiting rent increases from tenants while excluding others from affordable housing programs altogether.

At the urging of progressive lawmakers and tenant advocates, the White House has also flirted with capping rent increases at multi-family properties with a federally backed mortgage. Doing so would face many practical and legal hurdles, and the idea is still very much on the drawing board.

Quick Hits

- California's Department of Housing and Community Development released a new report on which jurisdictions are behind on their state-set housing production goals. State law requires that places not meeting their goals must streamline the approval of new affordable and mixed-income housing projects.

- At a House Oversight Committee hearing, Republicans laid into HUD for the department's lax oversight of public housing agencies.

- Two years on, New Haven, Connecticut's affordable housing mandate has gotten no new affordable housing units built.

- The mayor of Cranston, Rhode Island, vetoed a zoning change that would have allowed eight units on a vacant property, instead of the four allowed by current zoning. The mayor said allowing an additional four units was not "orderly growth and development."

- The California Legislature nixed a ballot initiative that would have repealed a section of the California Constitution requiring that new public housing be approved by local referendum.

- Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz criticizes YIMBY zoning reforms, saying that one person's freedom to build is "another person's unfreedom." OK.

- YouTuber Mr. Beast has built and given away 100 new homes. By comparison, San Francisco has permitted 16 homes thus far this year.

The post Gorsuch Apes NIMBY Government Lies in Supreme Court's <em>Grants Pass</em> Decision appeared first on Reason.com.