“Farmers are not against ecologists, in fact it’s the opposite - we want really high ecological standards in Europe,” Jean Matthieu Thévenot, a 30-year-old farmer in the French Basque Country, tells Euronews Green.

“As farmers, we are the first impacted by climate change because of the weather. We are also the first people impacted by pesticides \- farmers are dying from cancer due to this.”

As a representative on climate issues for European Coordination Via Campesina (ECVC) - a confederation of unions representing small-scale farmers \- he’s working with governments and institutions to strengthen environmental policies while supporting producers.

Here’s why he believes systemic change is needed to achieve this vision.

Farmers vs ecologists: ‘Manipulation’ by the agro-industry?

At the start of this year, Europe’s farmers made headlines when they took to city streets in protest. But their motivation was obscured, Jean says.

“You had this false opposition between ecologists from cities and rural farmers,” he says. “We think that's manipulation - this is the big industry trying to make farmers and ecologists fight together when the real problem is the industry itself.”

Rather than marching against green policies, small-scale farmers were demanding fair revenue for their produce, Jean explains. In most EU countries, the average income of farmers - including subsidies - is around half that of other citizens, according to ECVC.

But Jean says agribusiness lobbyists were keen to push a different message.

“They transformed these demands into ‘No, what we need is less environmental regulation, because that's the reason why farmers cannot make a living,’” says Jean.

While he agrees that it's impossible for Europe’s farmers to compete with international exporters who are not bound by the same strict rules, he says lowering standards to the same level is not the way forward.

“The solution is actually to ban imports that are not following our standards… and to set minimum prices,” says Jean.

For supermarkets, climate change ‘is not even happening’

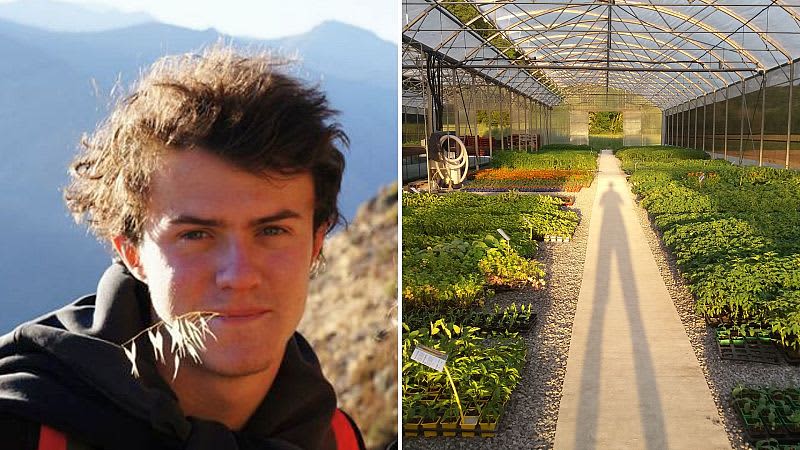

For now, Europe’s free trade agreements are rigged against local farmers whose output is suffering in the face of extreme weather. In Jean’s niche selling vegetable seedlings, he sees the direct impact of climate change on producers.

“Now it's clear for us that climate change is no longer something that will happen in two years - it’s something that's already here,” he says. The main issue is unpredictability.

In his region, an extremely wet and cold spring pushed this year’s tomato planting season into summer. But for supermarkets, it’s business as usual.

“We're fighting against the supermarkets and all the long chains because, firstly, we think they are responsible for climate change, because they emit a lot of CO2, and secondly, they are not respecting the farmers at all and not even caring about the situation.

“For them, I think change is not even happening. There are no tomatoes in France? They buy it from Morocco - at a really low price.”

‘Food is not a commodity’

In his work with ECVC, Jean advocates for intervention pricing from governments. This would force supermarkets to buy imported goods at the same price as local ones.

“We've always said that food is not a commodity. Food is the base of life, so it should not be included in the World Trade Organization system or in any free trade agreement because it's not a car, it's not a computer. It's something we need to live,” says Jean.

It would also benefit communities abroad.

“Let’s never forget that the main objective of the farmer should be local: they should first produce food for their citizens, and then if they still have [some left] they can export,” says Jean. “But at the moment we see the opposite. For example, it’s mainly cocoa production in some African countries, competing with traditional subsistence farming.”

He says the current system creates competition between farmers around the world - “and farmers are losing in the end, while transnational companies are winning.”

Jean is working with various academics to propose a new international trade framework “organised in a way that’s fair - based on solidarity and human values, and not on capitalism.”

Who will pay if food prices are regulated?

Regulated pricing would of course come at a cost.

“At the moment, the farmers are paying the price of the system - really low revenue, really harsh environmental conditions,” says Jean. But he emphasises that these costs shouldn’t simply be passed on to the consumer.

Instead, maximum profit margins should be placed on the big companies that are most responsible for mass production and the planet-warming gases that come with it.

Consumers do have a part to play, however, in their buying choices.

“Let’s continue importing tomatoes in winter if consumers [want them], but with a very high price so people realise it has an environmental and social cost,” says Jean. “Then if you want to buy local products that don't have these impacts, the price will be lower.

“At the moment it’s the opposite, so the cheapest product is the one with the heaviest impact… if we change,** consumers will be able to make the right choice.”

Though somewhat controversial, another approach is emerging in some small territories in France: the Sécurité sociale de l’alimentation (social food security) project aims to make things fairer for both farmers and consumers by pricing products according to customers’ income.

“So if you make a lot of money, you pay more, but if you make very little, you can take the veggies almost for free,” explains Jean.

He says it’s a winning model for governments, too.

“We’ve done the maths, and due to better farming and a better food system, in the end, it would save money that is currently spent on environmental adaptation, climate change mitigation and public health.”

What’s the solution to Europe’s farmer crisis?

As well as campaigning for price regulation, ECVC is rallying against what it calls “greenwashing tools to tick the boxes of the Paris agreement with zero guaranteed results”.

ECVC welcomes elements of the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy, which aims to build sustainable food systems. But it argues that it is at odds with trade and subsidy policies, and says its approach isn’t always credible.

The group takes particular aim at the EU’s Carbon Removals Certification Framework (CRCF), which it calls “scientifically invalid” and “dangerous for food systems”.

The regulation encourages ‘carbon farming’, offering subsidies and grants for farming practises that promote carbon sequestration in forests and soils - a temporary solution that sometimes relies on expensive tech unproven at scale.

It also supports farms in selling carbon offsets to companies - a counterproductive solution that creates “false confidence”, “delays real action” on emissions and “benefits polluters most of all”, campaign group Real Zero Europe warns.

ECVC warns that the scheme encourages land-grabbing by external players, worsening what is currently the biggest problem for Europe’s young farmers, according to Jean: access to affordable land.

Every rule from the government pushes you to grow bigger, to use more pesticides, to sell more.

The Commission’s resources would be better focused on “real, just and immediate reductions”, says Real Zero Europe, like a just transition to renewable energy and sustainable farming practices.

This could include supporting organic farming, crop rotation and farm autonomy, which would reduce CO2-intensive imports of things like animal feed, ECVC suggests.

“If you're a conventional farmer, every subsidy, every rule from the government will push you to grow bigger, to use more pesticides, to sell more, to export, etc. So we are pushed in that direction,” says Jean, whose one-hectare farm is too small to qualify for most subsidies.

Rather than favouring energy-intensive industrial farming, policies should protect small-scale farmers, whose operations maintain dynamic rural areas, prevent biodiversity loss and do not require huge amounts of fossil fuels or dangerous pesticides to operate.