The head of the national security department of the Hong Kong Police Force has warned of security threats going “underground” into arts and extremism despite the enactment of two security laws in the city.

Andrew Kan, the deputy police commissioner for national security, said on Sunday that security threats had “transformed” after Beijing imposed a national security law in 2020 and the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance was enacted in March.

“I think the threats have only transformed, they are still here,” Kan said in a Cantonese interview with TVB news. “We must remain vigilant and not fall into the trap of being unprepared for danger in times of apparent peace.”

Kan said that foreign interference led by the US and the West, which attempted to intervene in the city’s affairs such as court proceedings or the arrests of national security cases, was among the main sources of security risks.

But the head of the national security department also warned against “soft resistance,” a term introduced by a Chinese official and later adopted by officials, despite having no clear definition.

Kan said people who posed a risk to national security had gone underground because of the deterrent effect of the security laws, but continued to threaten national security.

“By using malicious words to create confusion, or through spreading fake news and disinformation in daily life, they mount soft resistance,” he said, adding that soft resistance “could be things like the internet, the media, the arts, watching a film or reading a book.”

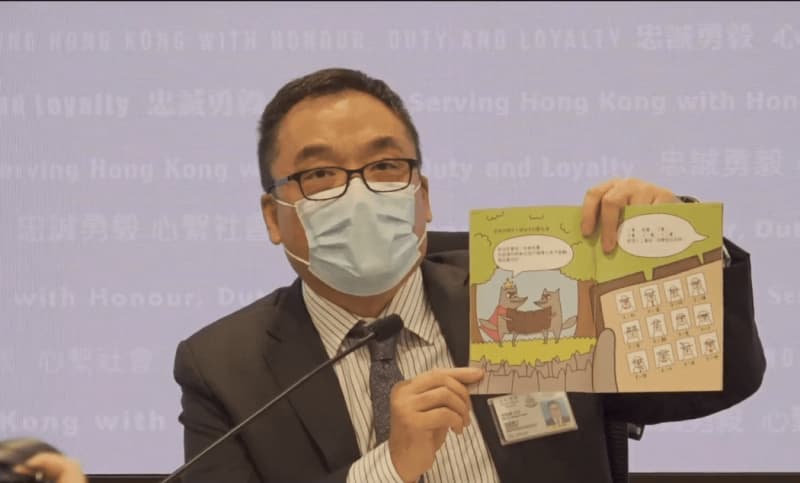

“On the surface it may not have breached the law, but if it oversteps a certain line, it is actually inciting people to break the law,” he said, using a series of “seditious” children’s books as an example.

Five speech therapists were jailed in September 2022 after publishing children’s books that pitted sheep against wolves in a fictitious village that the court ruled were “in effect brainwashing” young readers and carried a seditious intention.

In April, Secretary for Justice Paul Lam told the South China Morning Post that “false, misleading, unfair” statements were often at the heart of soft resistance. However, Lam added that there was “no legal means to counter [soft resistance], because what they are doing is lawful, no matter how much you dislike what they do.”

‘Local terrorism’

Kan also warned of “local terrorism,” saying extremists had gone underground but could return “when the time is ripe.”

He pointed to a man who killed himself after stabbing a police officer on the July 1 Handover anniversary in 2021, as well as the ongoing trial of seven people over a bomb plot to kill police officers during the 2019 protests and unrest.

Separately, Kan defended the national security police practice of reaching out to demonstration organisers, saying it dated back to before 2019, when the city was wracked by months-long demonstrations sparked by a controversial amendment to the city’s extradition law.

His remarks came in response to a question about activists having stepped back from protesting after being contacted by national security police. Last year, two former members of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, which disbanded in 2021, retracted their application for a Labour Day demonstration. One was suspected of being taken by police for several hours before the withdrawal was made.

“Understanding [a demonstrator’s] goals is key to our operations… Some people demonise this, claiming they have been threatened by national security police. I think they are trying to portray themselves as victims,” Kan said.

“It has nothing to do with us if they decide not to demonstrate. There’s risk assessment on their part for whether to demonstrate or not,” he said.

Kan also said the national security hotline – launched in November 2020 – had received over 750,000 reports as of June this year. Among them, 10 to 20 per cent were cases which warranted following up, he said, calling the ratio “very high.”

“The national security hotline has not received fewer reports over time, every month there is a consistent amount,” he said, adding that it showed residents’ regard and concern for national security.

Kan took office as the head of the police’s National Security Department last year, following his predecessor Edwina Lau’s retirement.

Beijing inserted national security legislation directly into Hong Kong’s mini-constitution in June 2020 following a year of pro-democracy protests and unrest. It criminalised subversion, secession, collusion with foreign forces and terrorist acts – broadly defined to include disruption to transport and other infrastructure. The move gave police sweeping new powers and led to hundreds of arrests amid new legal precedents, while dozens of civil society groups disappeared. The authorities say it restored stability and peace to the city, rejecting criticism from trade partners, the UN and NGOs.

Separate to the 2020 Beijing-enacted security law, the homegrown Safeguarding National Security Ordinance targets treason, insurrection, sabotage, external interference, sedition, theft of state secrets and espionage. It allows for pre-charge detention of to up to 16 days, and suspects’ access to lawyers may be restricted, with penalties involving up to life in prison. Article 23 was shelved in 2003 amid mass protests, remaining taboo for years. But, on March 23, 2024, it was enacted having been fast-tracked and unanimously approved at the city’s opposition-free legislature.

The law has been criticised by rights NGOs, Western states and the UN as vague, broad and “regressive.” Authorities, however, cited perceived foreign interference and a constitutional duty to “close loopholes” after the 2019 protests and unrest.

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team