By Hans Nicholas Jong

JAKARTA — Allegations of illegal activity and land-grabbing against Indonesia’s second-largest palm oil company continue to mount as a new report reveals the firm’s violations appear to be more extensive than initially documented.

The report alleges that subsidiaries of PT Astra Agro Lestari (AAL) are cultivating oil palms illegally inside forest areas; intimidating and criminalizing local community members; and operating without the required permits.

The report by Friends of the Earth U.S. and its Indonesian and Dutch counterparts, Walhi and Milieudefensie, respectively, is a follow-up to a previous report issued in 2022.

That earlier report looked at three AAL subsidiaries operating on the island of Sulawesi and found them to be engaging in land grabbing, environmental degradation, and the criminal persecution of environmental and human rights defenders.

The new report expands the scope by analyzing all of AAL’s known subsidiaries, whose operations span across Indonesia. It found more alleged violations, including operating plantations without permits and within areas that should be off-limits under Indonesian law.

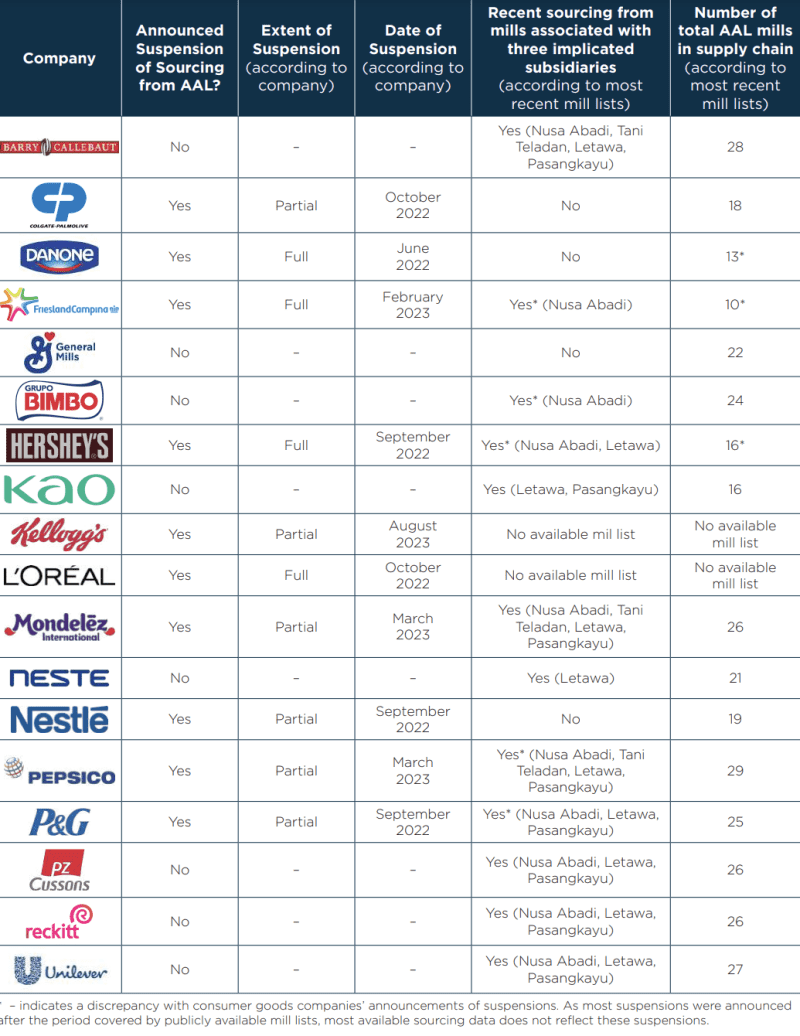

On the back of the 2022 allegations of environmental and human rights violations, at least 10 consumer brands suspended their sourcing of palm oil from AAL, with the latest to do so being U.S. food giant Kellogg’s. The cereal maker joined the likes of Hershey’s, PepsiCo and Oreo maker Mondelēz in distancing itself from AAL.

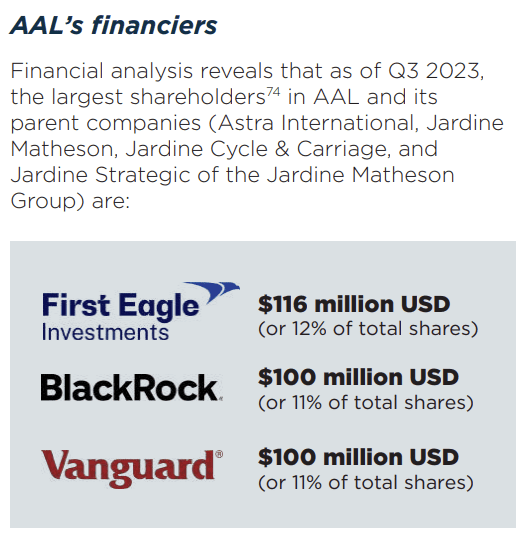

In addition to backlash from buyers, AAL also faces pressure from shareholders and financiers. In February, the Norwegian state pension fund cut ties with AAL’s parent companies, Singapore-based Jardine Matheson and Jakarta-based Astra International. The Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global was among the largest external investors in the conglomerate, with $236 million worth of shares in Jardine Matheson and Astra International at the end of 2022.

And last year, BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, voted against the election of AAL’s board of directors at the company’s annual shareholder meeting due to the alleged ongoing violations.

While a growing number of entities are cutting ties with AAL, major agribusiness traders like ADM, Bunge, Cargill and Olam still source palm oil from mills associated with implicated AAL subsidiaries, according to the new report. And at least 18 global consumer brands, including Unilever, Barry Callebaut and General Mills, have a recent history of sourcing palm oil from AAL.

And despite BlackRock’s shareholder vote, it continues to finance AAL and its parent companies, along with other financiers like Vanguard, HSBC and Dutch pension fund ABP.

The mounting allegations should prompt the Indonesian government to address the issue and prompt brands and traders still doing business with AAL to cut ties as well, said Uli Arta Siagian, the forest and plantation campaign manager at Walhi.

“AAL’s land grabbing, human rights abuses and illegal operations should be a wake-up call,” she said.

A pile of leftover palm oil husks behind PT Sawit Jaya Abadi’s factory, a subsidiary of AAL in Poso, Central Sulawesi, in March 2024. Image courtesy of Friends of the Earth.

Illegal plantations

Among the main findings of the FoE report is the existence of oil palm concessions held by AAL subsidiaries in areas zoned as forest, or kawasan hutan in Indonesian.

Forest areas are a government designation for areas that typically reserved for conservation and forestry businesses, and are meant to be maintained as a permanent forest. The only way to legally operate a plantation in a forest area is to rezone the area as non-forest, or APL, which requires applying for what’s known as a forest release decree from the environment ministry.

According to analysis of geospatial data and satellite imagery conducted by the NGO Genesis Bengkulu, 17,664 hectares (43,649 acres) of AAL subsidiaries’ concessions overlap with forest areas, mostly in Sulawesi.

AAL responded to the findings by saying that it had received forest release decrees to rezone those areas. However, these decrees may only be issued for forest areas categorized as “conversion production forests,” and not for those categorized as “protection forest” or “conservation forest.” The Genesis Bengkulu analysis found 1,100 hectares (2,718 acres) of the concessions in question were in forest areas that weren’t conversion production forests. That would make them illegal under Indonesian law.

In a May 2024 meeting between Walhi and the environment ministry, the latter confirmed that two AAL subsidiaries in Sulawesi — PT Pasangkayu and PT Letawa — hadn’t received the necessary forest release decrees for forest areas designated in 2014.

Letawa operates a 140-hectare (346-acre) concession in an area designated as conversion production forest in West Sulawesi province, while 617 hectares (1,525 acres) of Pasangkayu’s concession in the same province overlap with protection forest.

AAL said that in several cases, the government designates areas as forest area after a company has acquired all the permits needed to operate an oil palm plantation. If true, that puts the government at fault, since under Indonesian law, the state can’t designate an area as forest area if the company awarded the concession for that land already has the full suite of permits to start operating.

Either way, there are strong indications of permitting irregularities, the report notes.

Permit issues are a common problem across the palm oil industry in Indonesia, which the government is trying to resolve through a process of amnesty for companies operating illegally in forest areas. But no AAL subsidiaries are listed in the database of companies granted amnesty, according to the report.

AAL refuted the findings in general, saying they’re not based on the concession maps drawn up in the final permit that concession holders need to start planting, known as the HGU permit.

“Without HGU data or location permit data that’s verified, results of an analysis could be misleading,” Fenny A. Sofyan, AAL’s vice president of investor relations and public affairs, said as quoted by news portal Betahita.

The FoE report acknowledges not using the official concession maps found in the HGU documents, but points out that the Indonesian government refuses to make HGU documents publicly available — despite a Supreme Court ruling ordering the government to do so. AAL also didn’t share the concession coordinates, the report notes.

As a result, Genesis Bengkulu had to use well-referenced publicly available data for company concessions in Indonesia, from the forest-monitoring platform Nusantara Atlas. These, in turn, are derived from the government and cross-referenced with Greenpeace and World Resources Institute data.

The data irregularities and discrepancies in AAL’s concessions show why transparency is important in ensuring strong public monitoring of the plantation sector and detecting illegal operations, the report says.

“Until the Government of Indonesia ensures that land use data, including concession maps, cultivation permits, and other legal documents are made available to the public, companies will continue to hide violations behind arguments of data quality, leading to the continuation of land conflicts and corporate impunity for producers, and financial and reputational risks for financiers and downstream companies,” it says.

Palm oil factory owned by PT Sawit Jaya Abadi in Poso, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. Image courtesy of Friends of the Earth.

Permit problems

Even as AAL said it had acquired all the necessary permits for its subsidiaries, the FoE report reveals that some of them lacked HGU permits. Among them is PT Agro Nusa Abadi (ANA), which was identified in the 2022 report as not having an HGU permit.

This has now been confirmed by independent consultancy Eco Nusantara, which was commissioned by AAL in 2022 to investigate the allegations made by Walhi and FoE. Eco Nusantara concluded that ANA didn’t have the permit “due to the increasing problem of unresolved land disputes.”

The report also revealed two other AAL subsidiaries without HGU permits: PT Sawit Jaya Abadi (SJA) and PT Rimbunan Alam Sentosa (RAS).

“Given these disputes, the Indonesian government should review the permits of all AAL’s subsidiaries and, if AAL and its subsidiaries cannot substantiate their claims, should apply appropriate sanctions,” the report adds.

It says that any buyers, including palm oil traders and consumer brands, as well as financiers who do business with AAL are exposed to significant risks due to this absence of an HGU permit.

Members of the Plasma Partnership Cooperative on PT ANA’s palm oil plantation, a subsidiary of AAL, in March 2024. Image courtesy of Friends of the Earth.

Rights violations

The AAL subsidiaries’ operations have also affected local communities, with community members saying they haven’t been properly consulted on or consented to the concessions, the FoE report says.

According to the 2022 report, three AAL subsidiaries have illegally claimed or occupied more than 6,700 hectares (16,600 acres) of land in Central Sulawesi and West Sulawesi provinces without obtaining the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of local communities. But in its investigation into the allegations, Eco Nusantara chose not to look into the issue of FPIC, saying it wasn’t relevant as it wasn’t required at the time when two of the implicated AAL subsidiaries started operations.

The 2024 report called this “patently false.”

“Numerous international laws and frameworks make it clear that FPIC applies throughout the lifetime of operations of a project (and applies to impacts following the end of operations/projects),” the report wrote.

Furthermore, the fact that AAL is in conflict with local communities means FPIC is even more relevant and applicable in this case, the report adds.

AAL’s Fenny said in response that the group had consulted with communities “until we gain mutual agreement, or FPIC” as part of the process for receiving the necessary permits to begin operations.

However, the report notes that consultation isn’t the same as consent, nor a replacement for a process to obtain the FPIC of communities. And the fact that conflicts began when communities started facing negative impacts, including displacement from their lands, is evidence enough that impacted communities hadn’t given their consent, the report says.

“Companies can make rhetorical commitments to upholding human rights and achieving environmental sustainability, but talk is cheap — accountability is required,” said Gaurav Madan, a senior forest and land rights campaigner at FoE. “It’s clear that AAL never received the consent of communities to operate on their lands and is ignoring the right to FPIC.”

ANA, the AAL subsidiary that doesn’t have the HGU permit required to start operating, has been ordered by the local government in Central Sulawesi to relinquish 283 hectares (699 acres) of its concession to the community there. The order came in April 2024, after one and a half years and 26 mediation meetings.

“While communities’ and farmers’ claims to land taken by PT ANA and other AAL subsidiaries are considerably larger, the government’s action provides important precedent,” the report says.

In the face of the ongoing conflicts, affected community members have demanded that AAL and its subsidiaries return land to communities that was taken without their consent, and to compensate farmers for loss of land, crops and livelihoods.

Many of these individuals, however, say they face intimidation and the threat of criminal charges for speaking out. In December 2023, a video circulated showing two local women calling on AAL to return community lands. Two days later, AAL staff visited the women in Rio Mukti village and asked them to recant their statements — a sign of intimidation, the FoE report says.

AAL said that its staff was invited to visit by the village head to discuss individual support measures for community members, but that this was construed as an act of intimidation.

A villager of Rio Mukti in Donggala, Central Sulawesi, protesting against AAL in March 2024. Image courtesy of Friends of the Earth.

Corporate accountability

The report says AAL’s clients and funders aren’t putting enough economic pressure on the company to remedy ongoing abuses and future harms. By continuing to do business with AAL, it says, they’re effectively turning a blind eye to AAL’s alleged violations.

But international human rights norms mean these companies “have a responsibility to prevent and mitigate adverse human rights impacts ‘to the greatest extent possible,’” the report notes.

Consumer brands and agribusiness traders that buy AAL’s palm oil should suspend doing business and use their leverage to ensure land is returned, Gaurav said. And the financial institutions that continue to bankroll the company’s operations “should adopt agribusiness exclusion policies that shift investment away from the dominant, destructive model of monoculture plantations,” he added.

Consumer Brands Sourcing From AAL

In April and May 2024, a community leader and one of the women allegedly subjected to intimidation traveled to London to meet with representatives of Jardine Matheson, AAL’s parent company; HSBC, one of the banks financing AAL and its parent companies; and Unilever, the consumer goods giant that sources palm oil from AAL.

Yet even as the two community members were in London, security staff from an AAL subsidiary, PT Mamuang, visited their family members to inquire about their whereabouts. The family members reported feeling intimidated by these visits, FoE said.

Nevertheless, the meetings yielded at least one positive outcome. According to Walhi’s Uli, who accompanied the community members, Unilever said that while it didn’t have a direct business relationship with AAL, it acknowledged being exposed to AAL because it buys palm oil from Wilmar, which in turn sources from AAL subsidiaries.

“Because of pressure from us, [Unilever] is willing to urge Wilmar to investigate AAL, but there’s no action yet,” Uli told Mongabay.

While Unilever, which is behind many well-known household products and brands in the UK, from Dove soap to Pot Noodle, might not be a direct buyer of AAL’s palm oil, it still has responsibility to address violations made by AAL, with 27 AAL mills appearing in Unilever’s supply chain in 2022, said Gaurav.

Unilever told Mongabay that it had taken responsibility by engaging with relevant stakeholders, including FoE, over the past year in response to the grievances raised.

But in many cases, engagement done by big brands is simply not enough to provide remedy to affected communities, Gaurav said.

“Engagement is a means, not an end to itself,” he said.

Gaurav pointed out that many companies that have business relations with AAL have been tracking this case since 2022.

“Two years [have passed], but what have been the result of these engagements? Unfortunately for communities on the grounds, situation has not been improved,” he said.

Responding to the new report, Wilmar, the world’s biggest palm oil trader, said it repeats many past allegations against AAL, to which AAL had provided details and clarifications.

Gaurav said that’s not true as the new report contained fresh allegations and critically analyzed the lack of FPIC.

“For Wilmar to say this is just an old story and old allegations is ignoring reports that intimidation is ongoing and it happened as recent as May,” he said. “So I think Wilmar needs to take this seriously.”

Wilmar said it was aware of the allegations against AAL and its subsidiaries since October 2020, and had been engaging closely with the company since then to help resolve the concerns. It also said it’s currently reviewing the latest report from FoE and will respond accordingly.

In an email to Mongabay, Wilmar noted that AAL had invited FoE and Walhi to participate in the investigation carried out by Eco Nusantara and the resulting action plan, but that the NGOs had declined.

Gaurav said Wilmar’s claim is not accurate, as both FoE and Walhi had given inputs to AAL and Eco Nusantara on how the investigations should be carried out, which is focusing on the company’s land acquisition process, permit history and business operations.

But AAL decided to not consider the detailed recommendations made by FoE and Walhi, and not consult the affected communities in developing the terms of reference for the investigation.

As a result, the burden of proof was put on the communities during the investigations and the investigations didn’t examine the majority of grievances, including FPIC.

As an effort to address the ongoing concerns, AAL had developed a comprehensive action plan that covers conflict resolution, re-verification of community land within the concession, CSR program improvements and multistakeholder consultation in addition to accelerating HGU permit applications for areas / villages that are free from conflicts, Wilmar pointed out.

But since the action plan is based on the results of the investigations, it is inherently flawed, Gaurav said.

Just like the preceding investigations, the action plan was unilaterally decided and doesn’t reflect the demands for remedy and redress put forward by the impacted communities, which is for AAL to return their lands that had been taken without their consent, to compensate for any harms that had been done, and to recover the environment.

“On paper it looks good, but there’s no steps AAL is taking [in the action plan] to address the fact they never conducted FPIC process,” Gaurav said. “What they do say about FPIC is we will improve our FPIC process moving forward, which is great, but for communities who have lost their lands and have their family members thrown in jail, it didn’t address the issues.”

Instead, AAL’s action plan reflects a development model that places the well–being of communities in the hands of AAL, a private company, rather than recognizing communities as rightsholders with self–determination, the report wrote.

It also points out that failing to address the allegations of AAL subsidiaries’ legal, environmental and human rights violations puts traders and buyers at risk of not complying with a landmark EU antideforestation regulation, called the EUDR.

The EUDR, which takes effect in January 2025, requires companies importing into the EU to demonstrate that their supply chains are free of deforestation and illegalities. This includes ensuring respect for human rights and FPIC. Failing this, they risk being fined or even blocked from the EU market outright.

To ensure compliance, traders and consumer brands should stop promoting the expansion of industrial plantations like AAL and promote community forest management instead, said Danielle van Oijen, the international forest program coordinator at Milieudefensie, FoE’s Dutch counterpart.

“Continued sourcing from AAL carries risks of associated deforestation, illegalities and human rights violations,” she said. “Law enforcement bodies in the EU should thoroughly investigate all shipments with AAL products for compliance with the European Deforestation Regulation.”

Banner image: Members of the East Petasia Farmers Union on their land which is claimed by PT Agro Nusa Abadi (ANA), a subsidiary of AAL which doesn’t have a HGU permit, in North Morowali, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, in March 2024. Image courtesy of Friends of the Earth.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay